Normalizing the Price of Craft Work

- Suzanne Dekel

- Aug 19

- 3 min read

I just got back from a vacation in Normandy, France, and one of the highlights was visiting the Musée des Beaux-Arts et de la Dentelle in Alençon—the Fine Arts and Lace Museum.

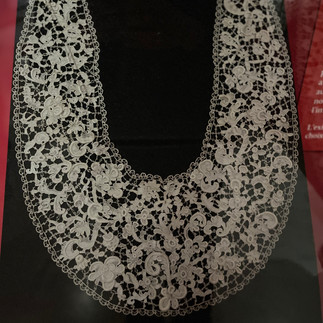

If you’ve ever heard of Alençon lace, you’ll know it’s something extraordinary. This style, also called point d’Alençon, is often referred to as the “queen of lace.”

Alençon lace has its roots in the court of Louis XIV. In 1665, Colbert brought Venetian lace makers to France so the king’s court would no longer rely on imports. From then on, the tiny town of Alençon became the center of a royally protected monopoly, producing lace for royalty, the French aristocracy, the Church, and later the European elite.

For over two centuries, Alençon lace was worn on collars, cuffs, gowns, and church vestments, always as a mark of wealth and refinement. Demand declined after the French Revolution, but it was revived under Napoleon and has remained a symbol of French luxury ever since. The technique is so intricate that UNESCO has recognized it as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This linen thread (produced specifically for lace making) lace can only be done entirely by hand with a needle and thread, no machine would ever be able to replicate the process. It’s unbelievably delicate, requiring tiny stitches and an incredible amount of patience.

At the museum, housed in the town's former Jesuit school, I watched a demonstration of this lace-making process. It’s mesmerizing and I know I would never ever have the patience for it; the precision, the rhythm, the way the lace slowly builds from nothing on a piece of sheep skin (which they remove afterwards). The lace maker explained that in the old days, one would be required to follow a seven year apprenticeship before one was allowed to start making lace. And here’s what struck me most: the museum doesn’t just sell lace; they sell it with a note explaining exactly how many hours went into making each piece.

And let me tell you; the numbers are mind-blowing.

A small piece of linen lace, maybe 5 centimeters wide, costs 310 euros. That may sound like a lot for such a tiny square, until you realize that it took 31 hours of skilled handwork to make. Do the math: that’s about 10 euros per hour.

To put this into perspective: as of 2025, the minimum wage in France (SMIC) is €11.88 gross per hour, or about €9.40 net after deductions. A lace maker producing one of the most rare and specialized crafts in the world is earning barely minimum wage, sometimes even less.

And if that’s what a small piece takes, imagine how many hundreds of hours go into the larger ones.

This was my biggest takeaway: we need to normalize including the number of hours in our price tags.

Because most people simply have no idea. They look at something handmade and think, Why does it cost so much? But when you show them: this scarf took 12 hours to weave, this embroidery took 40 hours to stitch, this lace took 31 hours for a piece no bigger than a match box, they begin to understand.

It’s not “expensive.” It’s fair.

So whether you’re making lace, dyeing fabric, weaving, or creating art of any kind, don’t shy away from telling people how much time it took. Put it right there next to the price. Educate them. I know this is what I will start doing from now on. Because once they see the hours behind the work, they’ll also see the value.

If a 5 cm square of Alençon lace carries 31 hours of invisible labor, how many hours do you think are hidden in the beauty of your own craft?